Lessons from a Billionaire Tech Pioneer: Early Backer of Hotmail & Tesla Reveals Profound Insights on the Adoption Curve

Here’s how you see things early and get in at the ground level.

This content is free because of readers who fund it.

If you enjoyed today’s letter, consider supporting me with a paid subscription equivalent to the price of a coffee.

It plays a pivotal role in sustaining my full-time writing career and producing better content—I genuinely appreciate your support.

Have you ever met folks who got in on opportunities ridiculously early and wondered how they pulled it off?

I’ve stuck closely to Tim Draper’s content because he hands you his playbook on a silver platter whenever he opens his mouth.

He’s a world-renowned venture capitalist who says there’s a way to spot investments that outperform, but if you use his strategy, you must be willing to “fail a lot”.

It’s easy to invest when everyone is piling into an opportunity but much more challenging when it’s an unproven concept. Before putting money into anything, he asks himself, “What could the world look like, and is that a world I want to live in?”

How Draper tells between what might appear like a shiny new thing vs something genuinely innovative is to ask the founder one question, “Why are you doing what you’re doing?”

He says the founder’s answer to this question tells him if it’s got a shot of breaking into the world, and “It filters out entrepreneurs where they’re not doing something that is fundamental or will change society or transform Humanity”.

If there’s a deep desire to “change the world” and make it better for the customer, and there’s a big enough market for it, those factors make him dive in “hoping to catch a wave.”

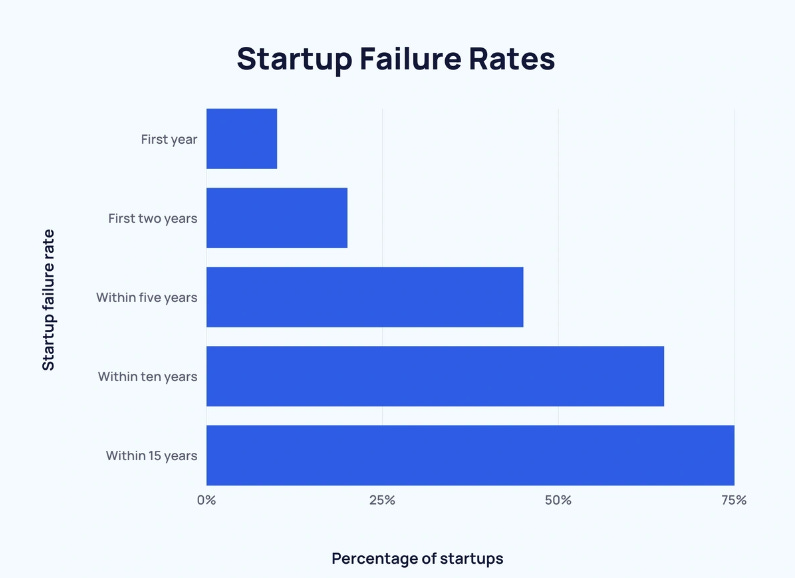

I’ve always been fascinated by how top investors manage to hit winners as often as they do, considering 90% of start-ups in America fail.

According to the latest data, out of the 8,775 financial tech firms backed by venture capitalists like Draper, 6,581 fail. That’s a 75% failure rate.

Of the 2,194 remaining, only 20 reach revenues of $100 million, which makes your chances of hitting a household name investment 0.22%. Yuck.

Given those odds, here are some names to put into perspective what a high-performing investor looks like, most you’ll be familiar with and investments Draper made during the seed rounds — Skype, Tesla, SpaceX, SolarCity, Ring, Twitter, Twitch, DocuSign, Coinbase, Robinhood, and Hotmail.

It reads like a hitlist of tech titans. Security would march you out of the casino if you had this many wins at the poker table.

Here’s the secret sauce

I’ve been tracking Tim Draper for a while now, and it’s safe to say his investing prowess is in a league of its own.

It’s also not luck.

He has the foresight to see things play out in society but the intuition to understand if the founder has the minerals to execute their grand vision successfully.

I once heard serial investor Garyvee say the best way to invest is to bet on the jockey first, then the horse second and it appears to be a strategy Draper follows too. The top of the totem pole of the hierarchy is always the founder.

Once Draper’s happy with the founder and ‘market fit’, there’s one more key ingredient.

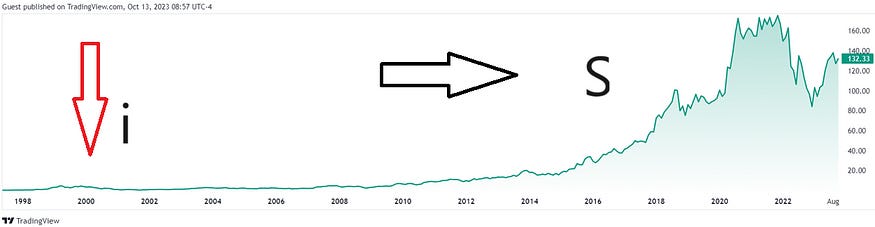

He calls it the “Draper I-S curve” and says new technologies follow the same trajectory: initial hype, a subsequent downturn, gradual improvement, and eventual widespread adoption.

Understanding this pattern gives you a headstart, particularly between the “i” and the “s” on a price chart.

Let’s dive into the juicy stuff.

The second mouse gets the cheese.

Tim Draper’s central tenet for investing is “The earlier you get in, the more uncertainty there is, but the higher your upside”.

He says with new technology as an investment, there is always a false start because people get a glimpse of how the tech could impact society, but the work to make it consumer-friendly still needs to be done.

So you have a window after the false start and before it takes off to make an effective investment decision.

Tim Draper —Source

“Almost every technology goes through the I-S curve, every industry comes up, gets hyped to the max, and that’s the dot on the “i”, so think of a cursive i.

And then it drops, and people complain about why it’s not good, like the Internet in its early inception. So, for years, it sits there languishing.

While that’s happening, all these great engineers are working hard and coming up with great ways for us to experience this internet thing. It slowly creeps up like an S, then explodes for years”.

You have more time than you think to get in on the ground floor before anyone else.

Most of us use Amazon daily, and it’s the perfect example of what Draper is talking about.

Amazon’s market cap rose from around $100 million in its first bull run during the dot-com bubble in 2000 to over $1.3 trillion today. That’s an increase of 1.3 million per cent (1,300,000%).

Following the internet bubble bursting, everything was overpriced and caused a global recession. If you had done your homework on Jeff Bozzo’s company, you still would’ve had 14 years from its market low to invest in Amazon before it took off like one of Elon’s rockets.

You still would’ve been early.

The “i” is so tiny you can’t see it on the chart — you could’ve taken over a decade to get in before monumental price increases and the “S” curve.

Closing thoughts

It’s a significant insight into how Draper has made so many winning bets ahead of time.

The reality is he’s not the first man in — he waits for the dot on the “i” to happen, then observes how founders and engineers build these products out.

Then, he reacts to something that has already happened and takes advantage of it.

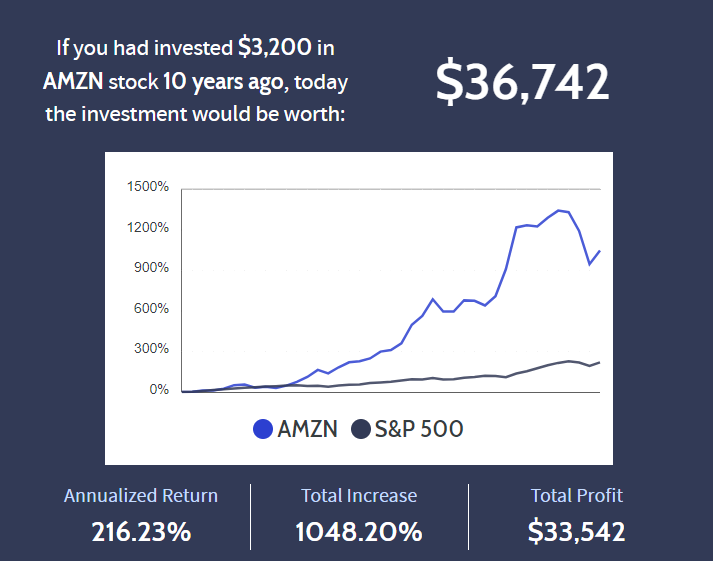

If you live in America, the average take-home salary is $ 3,200 after tax. For argument’s sake, if you had invested one month’s salary ten years ago, 13 years after the dot-com bubble burst and the Amazon cat was out of the bag, you’d have enjoyed returns of 1048.20% and a total profit of $33,542.

Numerous companies we rely on daily have surged like this over several years, even decades. You still had a lifetime to get in before it was “too late”.

For your everyday person, it’s a strategy worth paying attention to.