Your Fitness Sucks, Not Because You're Lazy but Because You're Getting Dopamine From All the Wrong Places.

Discovering the "negative reward prediction error" is something I wish I had known from the start.

Dopamine is at the heart of addiction.

When it's released, it's like your brain saying, "Great job! Keep doing that!" It helps you feel motivated, happy, excited, satisfied and rewarded.

This natural feel-good messenger was something I looked for in all the wrong places.

At my lowest point, when I weighed 101kgs and was clinically obese with a BMI of 34.1 (today I'm 77.9kgs with a BMI of 26.3), I'd wake up like a zombie in search of my first hit of caffeine before anything else.

A BMI above 30 is considered obese, while under 18.5 is underweight (BMI = weight in kg/height in meters²).

I'd jump in a hot shower, then do the 45-minute commute to work, park next to the hot sandwich van, and have my usual "sausage bap" with ketchup, which in U.K. talk means a metric ton of calories.

Then, about mid-morning, I'd get another shot in my main artery with a KitKat out of the vending machine washed down with a full-fat Coke.

Lunch times meant food had to be hearty like a jacket potato drowned in cheese with a chilli con carne topping and another can of sugary pop.

Then, between 3–5 p.m., when work was winding down and to keep me from falling asleep, I'd sneak in another chocolate bar with the spare change I had in the top drawer of my desk.

I was an addict, and I hated myself.

I transformed when I shifted my focus away from immediate pleasures, causing unhappiness. I rewired my brain to get dopamine from challenging things.

Let's dive in.

Authors Remark: I'm not a certified health and fitness expert — But as you can see, fitness, self-research, and using myself as a case study is my passion and the information contained in this article is all based on my personal experience, self-taught knowledge and deep research.

Stop using dopamine as the reward.

My day began like a person trapped in the clutches of substance dependency.

My opioids were caffeine, sugar, notifications on my phone and having four YouTube tabs open with short clips of David Goggins.

I used to get excited by anticipating a stodgy meal, and like clockwork, I'd feel horrific afterwards.

I've finally found out why.

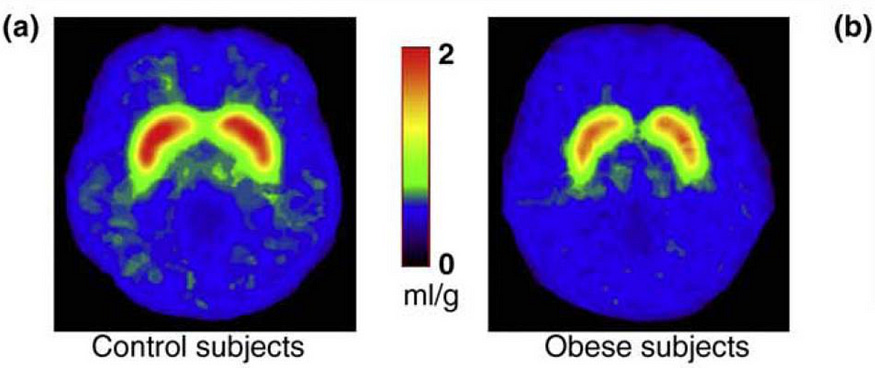

One research study showed that when obese individuals (e.g., my former self) see pictures of high-calorie food they like, their brains' reward and motivation areas light up more than people with average weight.

Their brain gets extra excited about the anticipation of the food like I did about an hour before lunchtime or pulling up to the sandwich van.

However, the study found when it came to actually eating the food, obese people's brain reward areas are less active than those of lean individuals. So, the pleasure they get from eating is less intense than they expected.

It leads to something called "Negative Reward Prediction Error". It's your brain's way of managing future expectations, motivation and behaviour.

When it comes to exercise, your brain says, "This reward ain't so good, so don't be as motivated next time."

Food is slightly different because, like social media, we think to fix it, we just consume more.

So, the outcome is — Obese people release less dopamine from eating food and enjoy it less.

Because there's a deficit in dopamine release, they try to compensate for the shortfall (like I did) by continually eating — it also makes them less sensitive to natural rewards, e.g. enjoyable activities, gym workouts, and long walks.

It's a cycle I can relate to because I'd often talk myself out of going to the gym or any physical activity.

Pictured is a dopamine release of obese people versus lean control subjects during the study when they ate their favourite foods.

Andrew Huberman, Stanford professor, Neuroscientist and famous podcaster, explains this phenomenon perfectly, and it's because, over time, we stop enjoying the things that once gave us joy.

If you're eagerly anticipating something, in my case, food, the experience doesn't quite meet your expectations when it finally arrives.

Andrew Huberman—Source

“If you’ve ever scrolled social media and you’re like, ‘I don’t even know why I’m doing this — it doesn’t feel that good’.

For people who aren’t feeling motivated, the problem is they’re not motivated, but they’re getting just enough or excess sustenance — they’re the opioid-like effects of constantly indulging oneself with social media, video games, food or with anything to the point where it no longer evokes the motivation and craving.

Dopamine should not be the reward but the build-up to the reward.”

Stop viewing dopamine as the start line.

Huberman says we all seek reward in the small, easy stuff. It's because we lack understanding of what dopamine does to the body.

He says humans pursue innately pleasurable things, like food, sex, and warmth.

We see the event or the celebration of the "thing" as the start line, but when we get there, we feel entirely unfulfilled. It perfectly explained my toxic relationship with food.

Huberman — "If you expect something to be great and it's not quite that great, your dopamine baseline lowers. And now, understanding what we know about dopamine, that means that not only did you feel as if you lost because it wasn't as much a celebration as you thought it would be (e.g. my lunchtime chocolate bars), but it also means that you're starting from a lower place, meaning you are less motivated."

Another research study found that we overestimate rewards, which explains why people can feel empty for months when they achieve significant feats.

It also lowers our expectations of the reward, making us less likely to try and pursue it. But with more minor things like food and social media, we make up for the deficit by consuming more.

Once you're rewarded, your dopamine levels drop below your standard baseline.

It explains why I felt like an utter slob after a meal with no ounce of motivation for physical activity.

Andrew Huberman — Source

“The person that’s not motivated, that can’t get off the couch, that doesn’t want to do anything well, this is the problem.

They are effectively the rat with no dopamine, but they can still achieve some sense of pleasure by consuming excess calories and social media.

When we can just sit there like the rat with no dopamine, gorging ourselves with pleasures, so to speak, what you end up with is somebody who feels really unmotivated, and those pleasures no longer work to tickle those feel-good circuits, and so there’s no reason for them to go out and pursue anything.”

Here's how you rewire your brain.

When I started running because of the pleasure of what it did for me, e.g. clearing my head from being in the office all day, I began to draw satisfaction from the process.

Unintentionally.

Instead of thinking of running as an activity for losing weight, i.e. the reward, I attached my reward to the process.

It's the prescribed way Huberman says we should approach hard things by finding pleasure "even if it's painful and doesn't feel good because that will stop us from avoiding doing the hard thing."

He says, "Internally, we must teach ourselves that effort is the good part — the anticipation of the celebration and progress. Not dancing at the finish line".

A profound psychological trick you can play on yourself is to access rewards inside of effort — like my running example, pursuing challenging and even painful tasks becomes more manageable.

Andrew Huberman — Source

“What’s more beneficial and can serve as a tremendous amplifier on all endeavours that you engage in, demanding things, is not to start layering in other sources of dopamine to get to the starting line but instead to subjectively attach the feeling of friction and effort to an internally generated reward system.

The keys are to pursue rewards but understand that the pursuit is the reward. If you want to have repeated wins the celebration has to be less than the pursuit, and that’s hard for some people to do.

If you can start to identify the craving as its own internally released drug, this thing dopamine that is a source of motivation, then you realise that capturing the reward is wonderful, but attaching dopamine to the reward is a little bit dangerous.”

Final Thoughts.

Understanding my dopamine-driven motivation was a game changer.

Had I known that my chocolate bar and coffee habit were a product of searching for my next dopamine hit and not that I "just had a sweet tooth" or couldn't "function without caffeine", — I might've changed course sooner.

I was unknowingly pursuing chemicals released in my body through daily habits that made me less motivated to exercise, which is why my fitness sucked.

It was not because I was lazy.

The self-destructive loop of relying on low-level feel-good sources like sugary food is one I'm free from.

I have created an internal reward system where I celebrate effort and the process.

So, no dancing too much at the finish line after a gym session. More dancing during.

Rewire your brain to see the pursuit as the reward.

It's a life-changing hack.